A sacred grove at Oorani? The satellite image of the small patch of green within a kissing distance of the surf-frilled coast of Bay of Bengal and 28 km from the former French colony of Pondicherry, close to the town of Marakkanam, is unlikely to provoke a second glance. Even if you had a thing for forest patches, you are very likely to move on – a postage stamp-sized green patch in the middle of insipid featureless coastal plain dotted with coconut plantations does not exactly draw your attention.

That, however, would be a huge miss.

This Oorani sacred grove, with a little imaginative leap, resembles a pair of lungs with the trachea running through (actually the road from Oorani village). This is sacred ground. It is one of the rare surviving patches of the TDEF (Tropical Dry Evergreen Forest, also called East Deccan Dry Evergreen Forests). While the eco-region for this intriguing forest type (essentially rain shadow areas in the Western and Eastern Ghats) cover more than 25,000 sq km, less that five percent of the original forest cover remains in any form or shape — mainly as disturbed reserved forests — and less than 1% is close to its original composition. The rest of the forest has degraded into tropical dry evergreen scrublands or nothing at all. The sacred grove near Oorani (the shrine devoted to Goddess Selli Amman) is one of the most pristine patches of TDEF – and it boasts a size of approximately 5 acres. That is exactly why it is difficult to spot, but it is something you wouldn’t want to miss, for it is perhaps your last chance to see it.

There isn’t a lot of literature available on TDEF. I had been collating and gleaning information off the net, then found access to some research papers through a friend, and picked up information from the Auroville website – and whatever little I learned piqued my curiosity. As far as the directions to the Oorani sacred grove are concerned, there aren’t any. Armed with the GPS reading and Google Earth on the mobile, we set out to locate the Oorani grove but pretty soon we were reduced the asking villagers for the Selli Amman temple. We were pretty lost until an alert villager told us about a grove that was occasionally visited by research students. A few more cautious queries and we were at Oorani.

As we walk down the narrow village road (freshly tarred and bisecting the grove), the first thing that grabs our attention is the Selli Amman shrine, which splits the road like a rock bisecting a stream’s flow. It’s a strange juxtaposition of the primal and the modern. There are two tridents, pierced with lemons, placed before the shrine and next to one of them are two bowls with dry powder — red and white — most probably kumkum and vibhuti. Next to the temple lies a clay horse, lovingly painted and then shattered in an apparent sacrificial offering. In a small forest clearing just off the road is an animist installation with a row of bricks dabbed with red. The temple is a small brick and cement structure with a Durga-like goddess figure on the top. It’s locked, with no one in attendance. By all appearances it’s an animist shrine with a recent veneer of contemporary religious iconography and seems to ooze primal energy from its dim interiors, which the dark forest absorbs as it broods in silence.

As we step into the grove, it takes a while to adapt to the darkness.

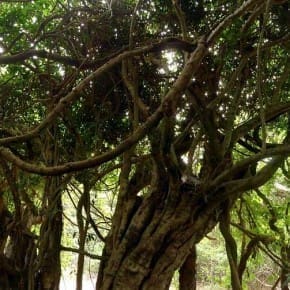

The trees are of moderate height and girth but dense enough to offer an impression of continuous canopy. The canopies of individual trees are thick and laden with vines. Huge woody lianas – thick as human limbs, snake around the forest, finding and holding onto the trees, spreading across the canopy, and then dropping back in thick ropes. The undercover is dark and an occasional shaft of light dazzles the sight. The undergrowth is moderate but wherever present creates dense woody clusters. The rest of the ground is carpeted with a beige-brown-rust-tobacco-maroon mosaic of fallen, bone-dry leaves that crackle at the slightest footfall. All over the forest floor ants and beetles are busy and if one creeps close to the ground there is the very audible rustle of the super-organism’s million feet on dry leaves. It is late afternoon and the darkness accentuates the impression of impenetrability while the twisting, entwining lianas weave an enchanted note that the silence carries till the edges of the patch. It’s a mesmerizing green oasis in a parched land – no wonder the aura bestowed sacredness and a modicum of protection.

Other than the fragmented remnant forest patches along the Coromandel coast the TDEF are found in Northeastern Sri Lanka, Thailand and Jamaica. The bio-diversity of these eco-systems is moderate when compared to the wet eco-systems but their restricted geo presence makes them critical for conservation. Researchers have listed about 20 trees and 13 liana species at Oorani and another survey that covered the 75 odd sites where any presence of TDEF is recorded, found 147 woody plant species and 47 lianas. Large numbers of these were medicinally useful. Notwithstanding this richness, TDEF are much worse off than the wet forests not just in India but the world over. The authors of a paper on TDEF ecology note that, “There is no single dry forest in the world that has not been used at least as a source of firewood or for charcoal production, and in the tropics 80% of all harvested wood is used for fuel purposes; the Indian dry evergreen forests are no exception to this. Resource removal such as firewood, fodder, medicinal plants, and timber harvest has been going on in all forests.” (R. Venkateswaran & N. Parthasarathy, Tropical Dry Evergreen Forests on the Coromandel Coast of India : Structure, Composition and Human Disturbance)

We step back on the road and walk down it turning left along the boundary of an incipient residential layout to the forest edge. The thick green, impregnable wall of foliage transitions into golden-red sandy soil bereft of trees or undergrowth (except replanted coconut and scattered tamarind tress). The forest ends as abruptly as it starts. All of a sudden the grove seems like a chunk of green mass leftover while the remainder was sliced off in portions by different hands through the ages. It survives since it was the core, the last curtain of the Goddess that somehow no one could muster the courage to tear off. The few fragments that remain (outside the reserved forests) along the Coromandel coast are almost all sacred groves — surviving cores of a must larger forest that ran along the coastline stretching up to 80 Km inland. Actually they may not be cores at all but shrines built into the forest that predate both — the modern worship and animism. The appearance of sacred groves may be simply due to the remnant forest clinging to the shrine while the larger forest that covered the land fell to unrelenting carnage through the centuries as human colonised the coastline.

As we walk back and pause at the shrine for a last look at the grove, now darker and silent in the late evening light, the sense of despondency is overwhelming. The initial joy of locating it and stepping into its majestic aura is replaced by the sadness of loss. The last stand of an ecosystem that predates humans, now brutally cut down to a few surviving pieces, is not easy to comprehend. The new residential layout, without a single tree and yet named Solaivanam, which rudely borders the eastern edge of the grove, does not help to lessen the injury (this layout has an opening on the ECR where the banners loudly proclaim a new wider road to Pondicherry and a proposed rail link). To mention that we need to restore the TDEF on a war footing seems fruitless — like howling at the wind. Whom would you comnplain to? Just a kilometre away as the crow flies, officialdom has lovingly tended a Eucalyptus monoculture 20 times the size of Oorani grove, classified it as a reserved forest and, taken in by their own worthlessness, built a guest house inside it. What can one say? As Bijoy says elsewhere on The Green Ogre: “Talk is cheap.” So, I’d better shut up.

References and further reading

Papers

Tropical dry evergreen forests of peninsular India: ecology and conservation significance

Sincere thanks to my friend Shanmugam Rajasekaran, who accompanied me on this trip and without his persistent efforts we would never have been able to locate the grove.

Text and Photographs by Sahastrarashmi

VIEW ALL PHOTOS AS A GALLERY

- Encounter: The Sacred Grove at Oorani - November 28, 2012

- Encounter: Rhododendron, sentinel of the highlands - October 7, 2012

- Manjhi Akshayavat, an immortal Banyan tree - July 17, 2012

Only second time I am reading about a sacred grove, very well written post. These small patches of Eden on earth hold the last surviving true biodiversity and need to be protected as both our heritage as well future.

Thanks, Prasad. It was a lucky find. But the threat to its existence are large.

Hello! Great article! Definitely informative. A good replanting effort is being undertaken by Govinda on Arunachala at Tiruvanamalai; he has studied TDEF very closely.

Also, you might want to tune into http://www.facebook.com/outreachecology — I have just begun 962 days of posting Landmark Indian Trees! Help spread the word about these wonderful Indian treasures!