On the 64th anniversary of India’s freedom, we wonder about the efficacy of captive breeding programs. Are they really worth it?

In the last six odd decades since Independence, India has been witness to the exploitation of its wildlife and natural resources along with apathy to diminishing forests coexisting with strident conservation initiatives. In this land of abundant wildlife, royals and nobles were enamoured with shikar. With ample help from their English masters, they brought about a rapid decline in the population of species large and small. In the latter part of our history, conservation programs have attempted to create safe havens for endangered species. Some conservationists have enthusiastically embraced the idea of captive breeding and reintroduction. Programs aimed at augmenting the wild population of the species have yielded mixed results. On Independence Day, we look at the issue of freedom in captivity. Does it really make sense?

The Himalayan Musk Deer (Moschus chrysogaster)

IUCN Categorization: EN –Endangered

|

| The last surviving Musk Deer (2006) at the Kedarnath Breeding Centre |

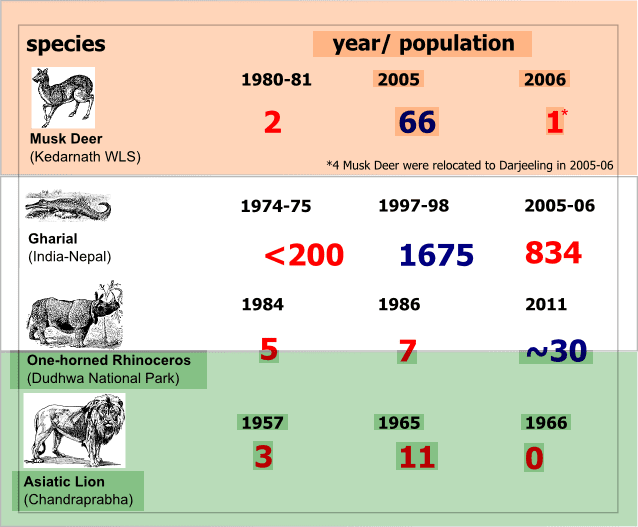

The Himalayan Musk Deer found in Jammu and Kashmir, Sikkim and Kumaon regions of India were extensively poached for the musk pods borne by male deer. A captive breeding program was commenced in 1980-81 at Kanchula Kharak in Kedarnath Wildlife Sanctuary, Uttarakhand with a pair of Musk Deer. Thirty years later the program has slipped into obscurity. In 2006, when Sahastra visited the breeding center, he saw the last survivor of the program. The fact that the Musk Deer had perished due to disease and climatic conditions, indicate insufficient monitoring of these parameters.

|

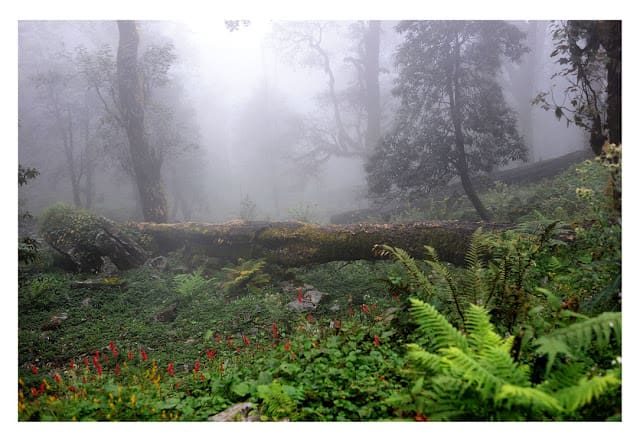

| Kedarnath Sanctuary in the Garhwal Himalayas protects critical Musk Deer habitat |

|

| Siberian Crane – The Lily of Birds according to A O Hume (image courtesy ICF) |

The Siberian Crane (Grus leucogeranus)

IUCN Categorization: CR – Critically Endangered

Siberian Cranes had three distinct populations at the turn of the last century: the Eastern flock migrating to China, the Western flock to Iran, and the Central flock to India which wintered in the Keoladeo National Park in Bharatpur, Rajasthan. The long migration routes of these birds make them vulnerable to hunting. In 1993 a captive breeding program was carried out with two captive bred Siberian cranes introduced to the Keoladeo National Park to unite with the migrant flock and return with them to the breeding sites in Siberia. The birds stayed back and subsequent attempts to introduce captive-bred birds to the migrating flock failed as well. As the Siberian Cranes form strong social bonds at birth, the plan to see the captive-bred cranes fly back to Siberia failed as the cranes did not get sufficient time to build new social bonds with the wild cranes.

|

| Siberian Crane (Grus leucogeranus) |

Gangetic Gharial (Gavialis gangeticus)

IUCN Categorization: CR – Critically Endangered

Gharials dwell in deep, fast-flowing rivers, which offer them abundant fish and sand banks for nesting. The threats they face are mainly from loss of habitat due to sand-mining, dams and irrigation projects, and hunting for their skin. In addition, depletion of prey fish due to overfishing has impacted the Gharial population. In 1976, after their population had dipped below 200 individuals, an effort in the form of Project Crocodile was launched for captive rearing of the Gharial. The National Chambal Sanctuary was set up in 1979 to protect the Gharial. Numbers have since dwindled after a major catastrophe resulting from pollutants in the river three years later, which resulted in the death of 113 animals. While captive breeding of Gharials has helped increase their numbers, it is imperative to safeguard the rivers that form the creatures’ habitat.

IUCN Categorization: VU – Vulnerable

Once ranging from the floodplains of the Indus to those of the Ganga and Brahmaputra, the Indian One-horned Rhinoceros was a familiar sight along the three great rivers. However, the fragmentation and destruction of its habitat for agriculture, and excessive hunting and poaching for its horn (which commands a huge black-market price as an aphrodisiac) saw the rhino population plummet, prompting stringent conservation efforts. As the majority of the rhinos are in Kaziranga, the skewed distribution of the rhino population adds to the risk of extinction in the event of a major calamity at Kaziranga. In 1984, a rhino reintroduction project was commenced in Dudhwa in a demarcated zone called the Rhino Reintroduction Area, which prevented possible conflicts between rhinos and the existing macro-fauna of the park such as tigers and elephants. A calf born in July is the latest addition to the rhino population. The phased approach to introduction with constant monitoring of feeding habits, spatial use patterns and other behavioral aspects has contributed to the partial success of the program so far.

Asiatic Lion (Panthera leo persica)

IUCN Categorization: EN –Endangered

|

| The lion lionised on an India postage stamp |

Records exist of the Asiatic Lion in Bihar, Delhi, Bundelkhand and Rajasthan. However, the lions in these regions were exterminated during the latter half of the 19th century. In the first decade of the 20th century, the only known population of the Asiatic Lion existed in the Gir region of the erstwhile princely state of Junagarh. The population has since sprung back in Gir and the renowned success story has prompted thoughts of the lions’ relocation to other regions in India like Palpur-Kuno in Madhya Pradesh. One such attempt at relocation was made in 1957 when a lion and two lionesses from Gir were introduced in the Chandraprabha sanctuary near Varanasi. The pride soon grew to 11 by 1965 before abruptly disappearing. This proves the feasibility of relocation for the Gir lions as the lions had survived for seven years following relocation.

• Forest Department, Audit Report for the year ended 31 March 2006 – Chapter III

• Protected Area Update – News and Information from protected areas in India and South Asia, Vol XVII, No 2, Apr 2011

• Gharial Gavialis Gangeticus – Colin Stevenson and Romulus Whitaker

• Gharial Our River Guardian – Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India

• Management of the reintroduced Greater One Horned Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis) in the Dudhwa National Park, Uttar Pradesh, India S P Sinha and V B Sawarkar, Wildlife Institute of India, Dehra Dun (UP), India

• The Great Indian One-Horned Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis Linnaus, 1758) S.P. Sinha

• Reintroduction of Greater Indian Rhinoceros into Dudhwa National Park – John B. Sale and Samar Singh

• Story of India’s Lions – Divyabhanusinh (National Centre for the Performing Arts (India), Marg Publications)

Text by Anand Yegnaswami

Picture credits :

Siberian Crane – ICF (www.savingcranes.org)

Musk Deer and Kedarnath: Sahastrarashmi

Other photos: Wikimedia Commons

Infographic by Beej