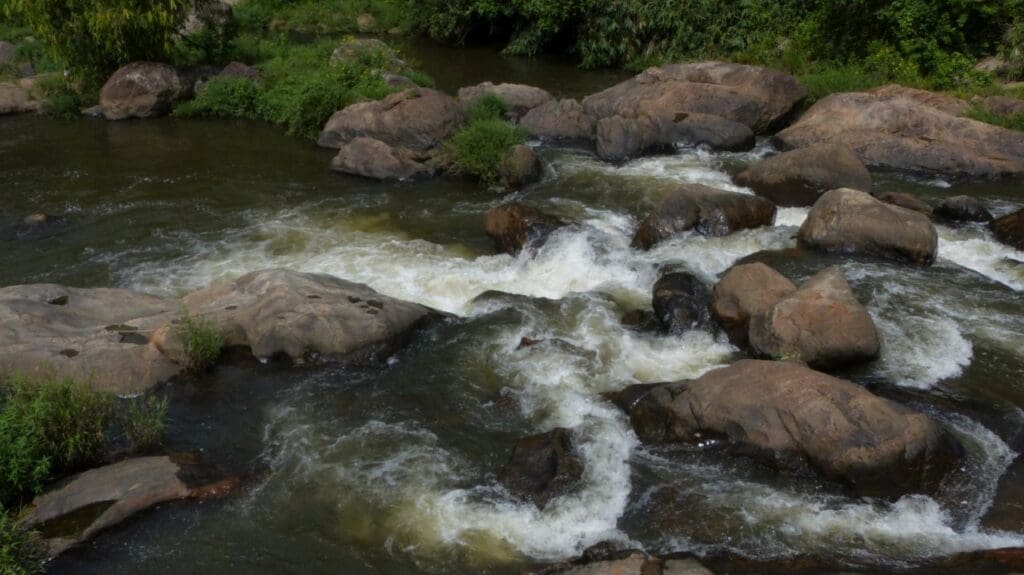

The Muthirapuzha is all of noisy pulchritude. One of three rivers that rise in Munnar and give Kerala’s charming albeit brutally oversold hill station its name (Munnar is Malayalam for Three Rivers), it bumps along a bed of time-smoothed rocks, thundering past the graves of primal rainforests, sour-smelling tea gardens, and decadent spice plantations ringing with the din of diurnal cicadas.

The birds are quieter, or maybe the river has deafened us to their dawn chorus. It is still dark when the Oriental Magpie-Robin begins singing his Lauds. At first light, a dolorous, hissy screech rings out from a ledge of one of the chalet-style cottages of the overpriced resort where I am lodged.

Then there is the outpouring of a whistling song, spirited and melancholy and hymnal all at once. It has a deeply human quality, ranging up and down the scale unconstrained by structure or meter.

I know that minstrel. But it is not always that I hear it sing like this. Or from so close. Its song drips like dew from a moss-girded trunk. When I lay eyes on it, it is unremarkable: In shape and aspect it is as dark as a crow, but with firmer, more insistent upstrokes in flight. It disappears into a crevice among the gables and I think I’ve seen the last of it.

For the Malabar Whistling Thrush, the fabled ornithologist Dr Salim Ali preferred a more poetic moniker — Idle Schoolboy. That name might not ring a bell to present-day schoolboys whose idle pursuits, sadly, don’t encompass the skinning of knees on gnarled tree barks, or the pleasant whiling away of time learning to whistle a tune, or putting a pen-knife to good use fashioning a flute from a reed in the hope of recreating that faun-like melody.

Those who have walked in the hills of southern India, particularly in the Western Ghats, know that the Malabar Whistling Thrush is — unlike most schoolboys — often heard but seldom seen.

Other schoolboys that these hills raised have left the memories of their home behind them. Unemployment has driven them to the lowland, where they learned entrepreneurship and skills that helped them harness and harvest the riches of the mountains. Homes have turned into home-stays, lodges into resorts, wayside tea shops into local cuisine hotspots — the scale of things has grown manifold. Prosperity of a kind is pervasive. And yet the hills have borne the brunt of it.

When we visited in May 2018, these hills were most definitely alive, sadly not with the sound of music to the ears. They were crawling with tourists like us. Holidaymakers thronged the attractions leaving trails of refuse, clogged the narrow town streets in their cars, and packed the resorts to the rafters. The hills have caved under pressure, often literally, and the scars of their suffering are everywhere, especially in the picturesque usury of tea gardens — a landscape that speaks more of ecological pillage than any other. For, while sipping their morning cuppa, few remember that in the late 1890’s, the British administration, with the patronage of the princely state of Travancore, cleared prime rainforest in the Kanan Devan Hills to plant tea, an exotic cash crop.

Monocultures of silver oak, eucalyptus and casuarina have taken the place of native evergreen forests in many parts of the Western Ghats. Yet, there are some treasured nooks where you can still listen to a forest stream whispering of times gone by as it runs softly through a dense shola woodland. In the margins between these violated landscapes, the survivors carry on singing. Southern Hill Mynas squeal joyously from the treetops, while a White-cheeked Barbet maintains a steady, punctuated rhythm.

Up in the heights of Top Station, the sanctuary at Eravikulam hosts some of the last surviving Nilgiri Tahr, although a casual glance at the animals grazing tamely on the hillside might give the mistaken impression that there are many more where they come from. Twice, two days in a row, we passed a herd of elephants grazing in a meadow, with forest department jeeps on the lookout for any sign of bad behaviour from man and beast. Increasing conflict between humans and elephants has tipped over the battle for the remnant resources — land and water, among them — to fever pitch.

Punctually, the wail of the siren at the Pallivasal pump house breaks the silence. The cormorant fishing in the stream takes wing. A fat raindrop fired from the sky like a warning shot misses a bumbling dragonfly resting on a bed of manmade litter.

I hear that anxious screech again. And again, at eye level from the window of my temporary lodging, I see that sprite-like shape again. In that cruddy light its form is dazzling – with highlights of electric blue against a satiny sheen of deep indigo-black.

Camera at the ready, I lie in wait on the balcony, a crick in my neck from too much peering and craning for a potbellied birder in his forties. Soon enough, Myophonus horsfieldii shows up, bill brimful of lichen, moss and twigs.

A nest is being lined in anticipation of a brood.

Soon, the rain will come. The southwest monsoon will drench these hills incessantly for months to come. Pouring in sheets and ropes and braids, it will infuse its magic, lending its voice to the river.

By then that schoolboy song will be a choir. What cheer!

A version of this post was first published on Medium. You can still read it there

- TL;DR – Death Stalks Like A Marabou Stork - July 24, 2024

- Dimorphic Egret – Meet this East African mystery bird - June 8, 2024

- Encounter: Northern Treeshrew in Arunachal Pradesh - May 19, 2024

One thought on “Song Sung Blue – A Malabar Whistling-thrush broods in Muthirapuzha”