I lost count at 8 or 9, but I estimate that Gunther got sprayed by a skunk on at least a dozen occasions. By the third time, I maintained a stash of hydrogen peroxide at home, ready to be mixed with baking soda and dish soap for a late-night hosing down of our ever-optimistic lab-rottie cross, the Mephitis mephitis’s olfactory cocktail of onion-sweat armpits, burned wiring, and dank weed searing a pathway deep into my brain.

Skunks, coyotes, hares, gophers, racoons, opossums, and even bobcats… when you hear about my backyard mammalian encounters, you’re probably going to place me somewhere deep in rural America, and not where I actually am, in the suburbs of Los Angeles.

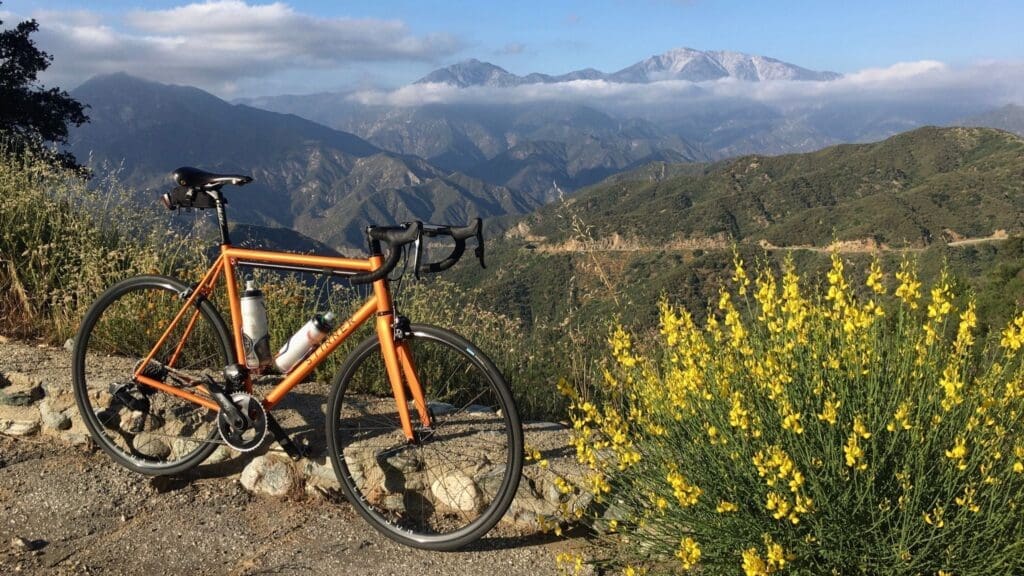

Thanks to the Transverse Ranges running west to east like a moody unibrow above the conurbation of LA County, more than 15 million people are within 90 minutes of a wilderness that can take your life if you leave your car without a plan. (As happened famously and recently to actor Julian Sands.) The steepness and ruggedness of these mountains keep them wild, allowing for the downhill urban incursions of everything from soaring turkey vultures to hungry black bears to raging wildfires.

Fighting the Devil’s Grass

In 2006, when we first came to Southern California, or SoCal as it’s known, the LA Times would feature stories of people being cited by their city for letting front lawns go brown. Or earning the ire of their neighbours for trading the conformity of mown Bermuda grass for spiky native gardens.

Today, after many years of drought, water restrictions, and climate reckoning, much of SoCal has given up on “the hissing of summer lawns”, as Joni Mitchell put it, allowing the sprinklers to fall seasonally silent: a summer browning that matches the colour shift of the chaparral on the overlooking mountain sides.

In order to immediately grasp what Joni—who settled in SoCal in 1968—is talking about, you perhaps have to be in a water-restricted yet decadent environment and be startled by the loud high-pressure hiss of lawn sprinklers coming to life; you and dogs switching to a trot to escape being hit by the overspray.

Many cities in LA County now pay residents to remove turf and put in native plants. LA’s suburbs are slowly freeing themselves of those manicured hood-ornaments of the American dream, replacing them with front yards that have an interest and character no monocultured, monochromatically verdant space could ever evoke.

My wife and I did the same with the tangled carpet we inherited from the previous homeowner, working with Natural Earth, a local “sustainable landscape and design” company, to shape the land to direct and hold rainwater, and, in an act of topographical sprezzatura, sprinkle the garden with rocks and native plants.

But first came war.

Bermuda grass is rightly also called devil’s grass. Its roots go deep and wide. Miss a tiny underground rhizome, and a green web spins itself across the ground in days. Eliminate every one of these, and devil’s grass will still claw its way up from under rocks, walls, and cracks in concrete, sending out grasping stolons in search of chinks to drop roots and recolonise the landscape.

Bermuda grass is rightly also called devil’s grass. Its roots go deep and wide. Miss a tiny underground rhizome, and a green web spins itself across the ground in days.

It took the petrol power of mini-bulldozers, followed by the square foot by square foot sifting of the soil by Natural Earth’s ground crew, but eventually, field sedge replaced devil’s grass, creating a soft backdrop for local plants such as toyon, big berry manzanita, and, in the centre of the space, a young Fremont cottonwood tree.

These Roots Take Time

“Be patient.”

Every information source about native gardens tells you this. California natives spend their first couple of years developing extensive root systems, with little to no activity above soil level. Water them occasionally but deeply, and “hodl, hodl, hodl,” as the crypto bros say, and you will be rewarded with a slow-motion explosion on that third spring, with California poppies at the fore, joined by yarrow, monkey flowers, lupines, sages, milkweed, and finally, in late May, the peaking of the “fried-egg flower”, or Matilija poppy.

One of my favourite plants is the sacred white sage; tubed bushes so powerfully aromatic that our little bluenose pitbull, Rupert, comes to bed redolent from his wanderings. Salvia apiana’s insect-shaped white flowers are especially attractive to representatives of California’s 1,600 native bee species (none of them a honey bee, they’re all loners). Hummingbirds love these blooms too, and when they’re not dipping their beaks, I’ll often see these Snitch-like beings scream through the garden at head height, pulling high G’s through the California live oak to hover among the topmost branches. Sometimes you’ll hear, almost feel, that throbbing wing beat and turn to see one parked in the air four feet from your head. If I’m lucky, I spot the crimson glister of an Anna’s hummingbird catching the light like the sequined dress of a Vegas showgirl winking from the wings.

Now that there are bushes, rocks, and other hiding places for lizards and insects, there’s more interest and excitement from the usual suspects: the black phoebes, California towhees, California scrub-jays, northern mockingbirds, and, keeping a stern eye on everybody from the top of the tallest tree, a pair of Cooper’s hawks.

One of my favourite plants is the sacred white sage; tubed bushes so powerfully aromatic that our little bluenose pitbull, Rupert, comes to bed redolent from his wanderings.

Thanks to both a seasonal mindset and plants that need less, our water bills have shrunk, as has the need for mechanised garden maintenance. Dead vegetation stays, instead of the ridiculous open loop of feeding the ground to grow grass to cut it to throw it away. With a system in balance, we have vastly fewer nuisance insects, especially the midges and black flies that make it nearly impossible for our be-lawned neighbours to even be outside on warm days.

But best of all, we now have a garden I can—sundowner G&T in hand—sit and watch. I work from home, and any time I go from my backyard office to the house, there’s something to stop me. Perhaps a monarch butterfly laying eggs on the milkweed; a bumble bee comically bending each poppy over with its great weight; or simply another errant dandelion that I detour to pull out by the roots.

Here in SoCal, we need to fully open our eyes to the classism and criminal waste that is the hissing of the summer lawn.

However, I need to accept that this is a seasonal pleasure. So far inland, away from the fashionable Westside LA attractions you visit on holiday, summer temperatures are in the high 30’s Celsius, sometimes even breaking into the 40’s, with no precipitation for six or more months. Many of the plants I’ve mentioned go dormant (i.e. “die” to my inexperienced eye), ready to resuscitate after the first winter rains. The perennials do fine with little to no extra water, just getting a little drab through the hottest months. This is a season just like any other, and here in SoCal, we need to fully open our eyes to the classism and criminal waste that is the hissing of the summer lawn. A brown front yard should be no more onerous and inevitable than, say, one covered in muddy, half-melted snow.