|

| the beauty with large eyes! |

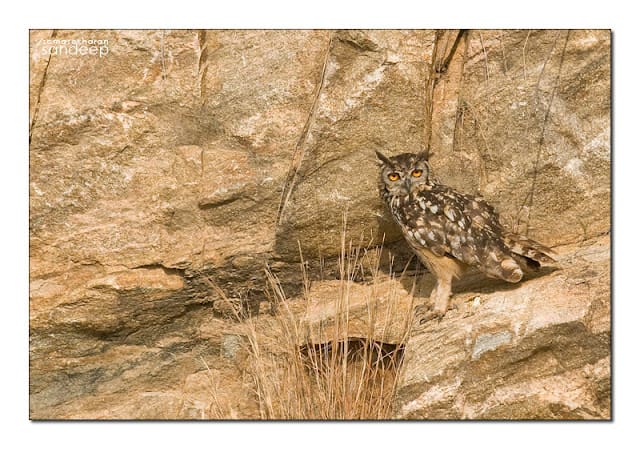

My love of owls has made me peer into abandoned quarries, tree hollows, rafters of old barns, and dilapidated houses. In one such quarry in the outskirts of Mysore I saw a fully grown female Indian Eagle Owl, which perched on the least noticeable ledges and watched us with her large, all-perceiving eyes. The spell she cast on us was unbreakable, so much that we continued to pay her frequent visits.

Generally she would be quite shy, taking off to distant inaccessible corners of the quarry if we got close. But on one visit in January last year, she didn’t leave her perch, however close we approached. The ledge, though, was inaccessible – it was about 10 feet high and about 7 feet away from the edge of the deep rainwater pool at the bottom of the quarry. We imagined the reason for her perceived acquiescence was that she might be nesting. We left her alone.

|

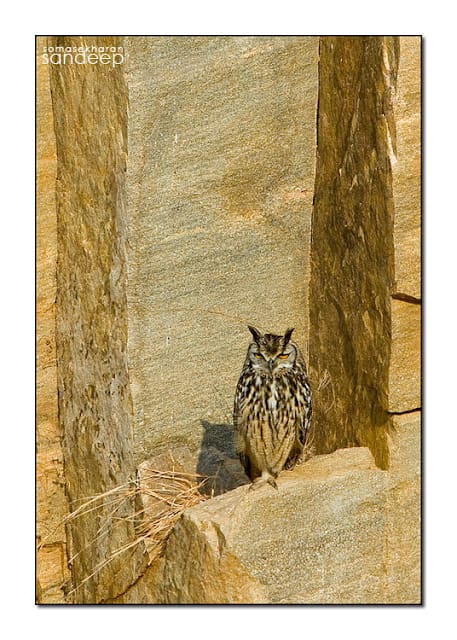

| Momma squints a warning |

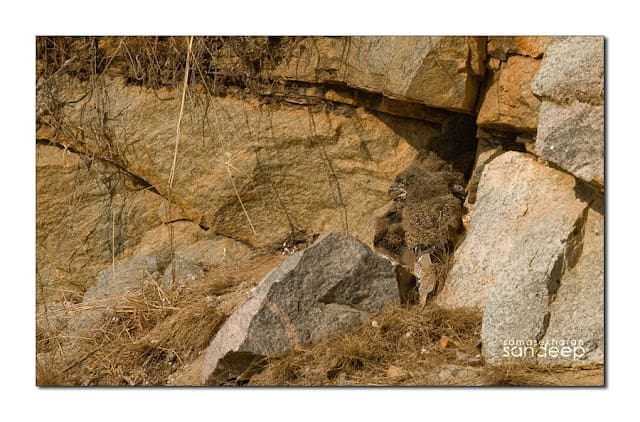

A few weeks later, in February, we returned. The mother was nowhere to be seen. Scanning the ledge carefully corroborated our guess: three tiny feather-balls. My heart thumped. The sun was coming up, and the chicks were pushing against the farthest corner of the quarry wall, seeking protection from the early morning sunlight that was now turning harsh. The nest was a humble setup — a ledge with sand at the bottom and some grass growing at the edges. Mommy showed up presently, her stern stare radiating a warning: “Keep off!”

|

| Huddled in the nest and vulnerable. |

|

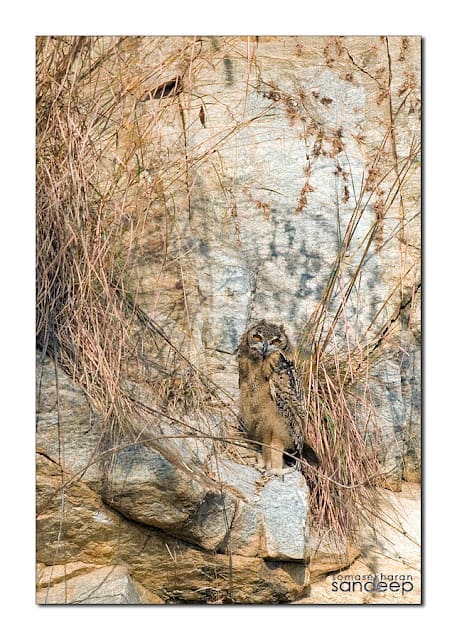

| Momma plays sentinel |

When we next visited the quarry a month later, in March, we couldn’t spot any chicks. Dismayed that they might have died of illness or fallen to predators, we prepared to leave when we spotted a chick behind the grass stalks that jutted out of a ledge. It appeared to be three times larger than we had last seen it. Another sat a few feet away on another ledge. There was no sign of the third (we never saw it again). Mommy occupied another ledge, watching us intently with the same stern schoolteacher expression. Since the chicks were on a different ledge from her, it was pretty obvious that they had started to fly.

|

| Well concealed |

|

| And the second chick on another ledge |

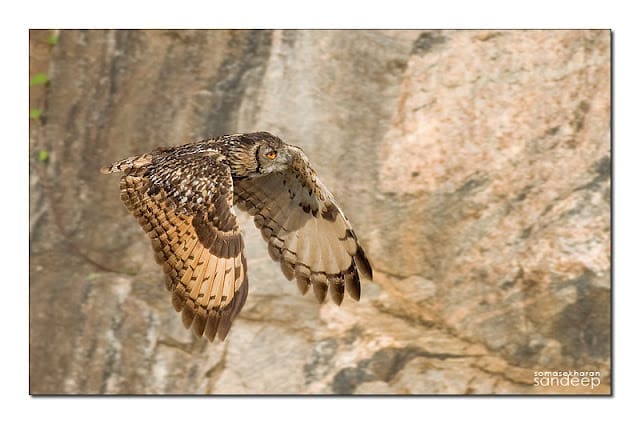

Our next trip to the quarry happened only in May as something or the other interfered with our plans. All we saw were two adults: The larger mother and the other was probably one of the chicks, which had by now grown large enough to be on its own. The second chick had probably left the quarry (or maybe it was dead — we would never know), and I had a feeling that I would not see this one for long either.

|

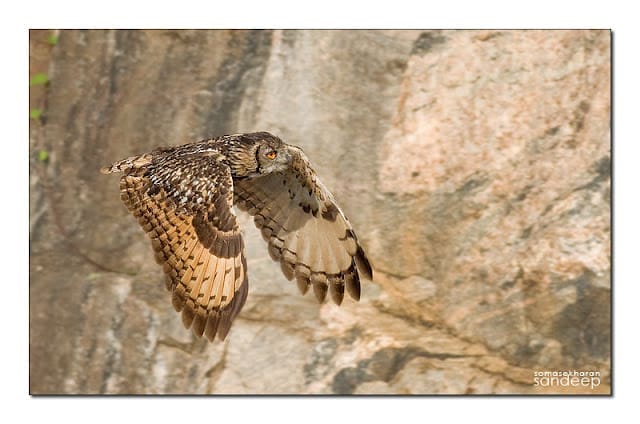

| The little one takes flight… |

|

| The last glimpse that I got of the young owl |

As expected, on later visits we found only the mother owl. Since Eagle Owls are voracious eaters and require a large area to hunt in, it is likely that the grown chicks had left to set up their own fortresses elsewhere. I do think about them once in a while, wondering where they would be now, whether they managed to survive and found happy hunting grounds of their own beyond the reach of superstitions or predators.

After all, when babies grow up before your eyes, you get attached to them!

Further reading:

- An excellent technical documentation of Eagle Owl chicks [PDF], by Eric Ramanujam and T Murugavel, is available at the Journal of Threatened Taxa website.

- Sad, Wise Eyes, an article about owl trafficking by Shruti Ravindran, appeared in the March 2009 issue of Outlook magazine.

Text and photos by Sandeep Somasekharan

More on The Green Ogre:

Read more about Indian Eagle Owls and Barn Owls

Read more about threats to Mysore’s scrubland habitats

- Costa Rica Diaries – Parting Gifts - May 5, 2024

- Costa Rica Day 6 – Resplendent Quetzal: Part Bird, Part God and Full-Time Economy Driver - April 17, 2024

- Costa Rica Day 5 – Toucan Trees and Wild Dreams Coming True - March 22, 2024

Thanks for your comment, flowergirl. Our website has been upgraded recently. Do sign up for updates: http://eepurl.com/m-iHX

Hi Samyak,

Thank you for your comment. Do share more details about your owl documentation. Meanwhile, our website has been upgraded.

Do sign up for updates: http://eepurl.com/m-iHX