A chance find in a Pondicherry flea market points to an unknown Tamil Nadu pilgrim party’s mysterious journey to the base of Mount Kailas in 1948, only two years after Heinrich Harrer arrived in Lhasa

Last Sunday, as I am prone to do on weekends, I paid a visit to the flea shops on the East Coast Road in Pondicherry. These shops, which usually offer a motley collection of old stuff – terracotta figurines, calendars and posters, furniture, French porcelain, old black-and-white photographs, books and the usual bric-à-brac, sometimes throw up a surprise.

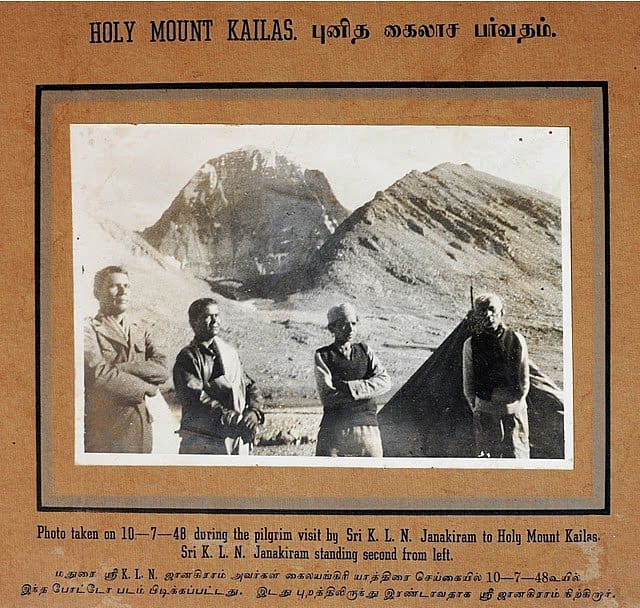

Rummaging through an old tin trunk full of dusty faded black-and-white photos I came across an old, slightly faded picture with a mountain in the background. That was surprising enough – 90 percent of the pictures are usually studio portraits of respectable South Indian families, newlyweds, demure housewives and pious Brahmins – but what hooked me was the familiar outline of the peak. From its aspect, it could have been only one mountain — a huge mass of rock and snow, magnificent in its setting, awe-inspiring and bequeathed with majestic grandeur. It was Mount Kailas (6714 m).

My heart pounded as I dusted the picture and read the text printed on the mount: “Photo taken on 10-7-48 during the pilgrim visit by Sri K. L. N. Janakiram to Holy Mount Kailas.” Four men stood in front of the mountain, three looking away from the camera with the canvas tent visible behind the fourth person. The four pilgrims appear in good shape, proud but with no visible swagger at this achievement, which even in these times when Toyota Land Cruisers race down to within shouting distance of the holy mountain, is a matter of undue vanity and arrogance for quite a few.

To put this in context, the region was still being explored in the late 1930s. A paper written in 1942 by the eminent geologist Darashaw Nosherwan Wadia (after whom the Institute of Himalayan Geology was renamed in 1976), mentions explorations carried on between 1928 and ’38 in the Kailas-Manasarovar region as having “raised some doubts regarding Sven Hedin’s conclusions [the Swedish geographer, explorer and writer was the first European to enter the Kailash-Manasarovar region]. Though not a professional geographer, the Swami [Swami Pranavananda, whose book Exploration in Tibet attempted to surmise the sources of the Himalayan rivers] has made a record of most interesting, accurate and painstaking observations of natural features and phenomena which provide valid data on the intricate question of fixing the sources of these rivers”.

The rivers spoken of are the Indus, Sutlej, Ganges and Brahmaputra. Heinrich Harrer’s fabled escape to Tibet via the Tsang Chok-la Pass (5,896 m) near Badrinath was made only in 1944 (he reached Lhasa on January 15, 1946).

Partly due to its remoteness, but mainly since Tibet was closed to foreigners through much of its history, the chronology of first explorations of this mysterious Himalayan kingdom is as intriguing as the land itself.

While trade between India and Tibet, conducted during the summer months once the high passes were free of snow, has a long history, the first Europeans on record to visit Tibet were probably the Jesuit monks António de Andrade and Manuel Marques from Portugal who arrived in Tibet via the Mana Pass near Badrinath. This was in 1624 during the reign of the Mughal Emperor Jehangir. They set up a short-lived mission in Tibet and their travel accounts were quite popular in Europe where they were translated into all major regional languages.

Between 1893 and 1908, Hedin led three expeditions into Central Asia and Tibet. During his second expedition (1899-1902) he was unable to reach Lhasa, being turned back by the Tibetan army, he exited via Ladakh continuing to to Calcutta via Delhi, Agra and Benaras. During his third expedition (1905-1908), he became the first European to reach and explore the sacred Kailas and Manasarovar region of Tibet. He was also credited with locating the sources of the two greatest rivers of Asia – the Indus and the Brahmaputra (a discovery that was later questioned – he may have found one of the sources).

The British, who were not allowed entry into Tibet, worried that other European powers would beat them to it (the Russians were persevering hard to enter Tibet). They trained and sent several Indians from Johar Valley in Uttarakhand to carry out surveys in Tibet. Between 1865 and 1882, Nain Singh, Mani Singh, Kishen Singh and later Kinthup (from Sikkim), disguised as Ladakhi merchants, undertook several undercover survey missions to Tibet, explored the land (they were trained to cover a fixed 33-inch pace and click a bead after every 100 paces), measured the altitude (by measuring the boiling temperature of water, mercury was hidden in a cowrie shell and the walking stick a makeshift thermometer) and coordinates of Lhasa , surveyed the Manasarovar region, and successfully determined the course of the Sutlej river and the upper course of the Tsangpo.

One gets an idea of how little was known about Tibet despite all these attempts by the fact that until 1912 it was not known if Tsangpo in Tibet was the same river as the Brahmaputra in India. In 1878, Kinthup was specifically sent to Tibet for this reason but despite his valiant efforts this mission met with a tragic end. He was to float 50 specially marked logs a day for 10 days down the Tsangpo. Surveyors were to lie in wait for these logs on the Indian side in Arunachal Pradesh. However, first he was duped and sold as a slave by his fellow-traveller. Then, 18 months later, when he managed to flee his captors on the pretext of a pilgrimage, his letter to his handlers never reached India. He floated the logs and when he finally returned, his hunch that the Tsangpo was indeed the Brahmaputra (he correctly described the river as it rounded the huge peak of Namche Barwa, 7745 m, entering a deep gorge within a short distance of the Indian hills) was met with scepticism. The gorge described by Kinthup is now known as the Yarlung Zangbo Grand Canyon – the world’s deepest canyon where the Brahmaputra cuts through the Eastern Himalayas to enter India.

I could learn very little about the routes taken to Kailas during the days of British rule. Several options existed via the Mana pass (5608 m, near Badrinath), Lipulekh (5334 m, the current route), via Leh over the Changtang plateau, from Sikkim via Nathu La (4010 m) and via Bhutan, or from Nepal. I can only guess the route that this party from Tamil Nadu could have taken. But regardless of that, they would have faced lawless bandits, inclement weather and the perils of uncharted routes. It’s a testimony to both their endurance and faith that this journey to the abode of Shiva was a success.

While I feel sorry that the photograph of these four pioneer pilgrims ended up in a flea shop, as someone who is completely taken in by the mystique of the Himalayas, it is a perfect gift. The photograph has finally come home.

Main Photo: Unknown

References: Trekking in the Indian Himalaya (Lonely Planet). For pictures of turn-of-the-century Tibet, visit The Tibet Museum

Traveller, photographer, philosopher, art connoisseur, trekking guru, and master trip planner, Sahastrarashmi (SR or Sahastra to his friends) is on a relentless quest for the story of life. An engineer from the Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur, he works in Chennai, India and lives (on weekends) in the former French enclave of Pondicherry (Puducherry to the officious). He is on a mission to introduce the uninitiated to the glory of the Himalaya.

-

Traveller, photographer, philosopher, art connoisseur, trekking guru, and master trip planner, Sahastrarashmi (SR or Sahastra to his friends) is on a relentless quest for the story of life. An engineer from the Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur, he works in Chennai, India and lives (on weekends) in the former French enclave of Pondicherry (Puducherry to the officious). He is on a mission to introduce the uninitiated to the glory of the Himalaya.

View all posts

Enjoy more stories

Go to the antMy mind's been besieged by ants. I used to watch ants a lot all of…

-

-